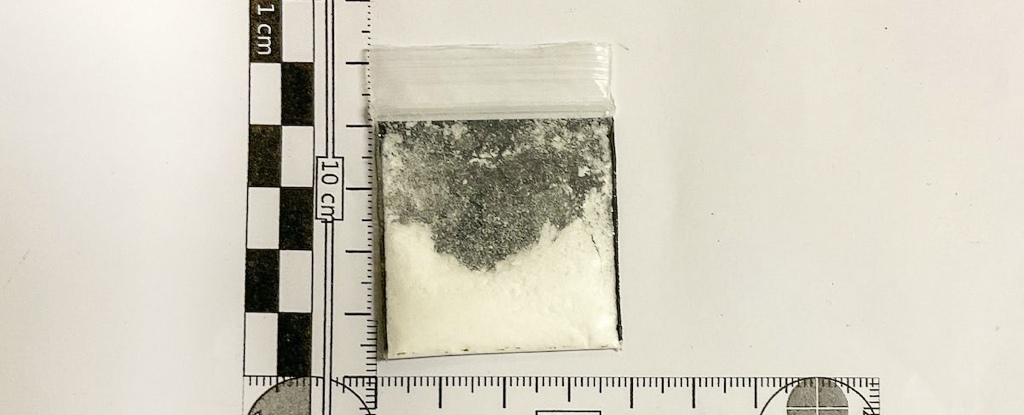

You can imagine a small plastic bag containing a mix of powder and crystals.

The person who presents it believes that “it might be.” ketamine?”???? ‘, but acknowledges that the subjective effects can be different from what they are used to. How can we determine if they are right? What are the consequences for it not being?

This is the typical situation for people who work at CanTEST – Australia’s first and only fixed-site, face-to-face drug-checking service, located in Canberra.

This led to chemists discovering a drug not seen before in Australia. There was no clinical information available from the rest of the world.

Identifying “chemical X”

The identification new psychoactive substances – drugs made to resemble established illicit drugs – presents a major challenge when pill-testing. We can test a chemical to determine its fingerprint, which will hopefully match one the thousands of databases that are available to us analysts.

What happens if a fingerprint does not match the query and we find ‘chemical X?

This brings us back the original bag of powder.

Patrick Yates, a PhD candidate from the Australian National University’s Research School of Chemistry, ran the sample through the first piece of equipment, the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer – a workhorse of many drug-checking programs around the world.

FTIR works quickly and reliably – even at a Bush doof – as long as an electricity supply is available. The laser shines on the sample and captures the “reflection” (a measure of the drug’s shaking and movement). This is then compared with a database that contains more than 30,000 chemicals.

Patrick’s analysis of Patrick didn’t confirm a match for ketamine, but suggested that there might be an older ketamine analogue. 2-fluorodeschloroketamine (2-FDCK). Patrick’s trained intuition made him doubtful.

Cassidy Whitefield, a PhD student, then turned to ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) with photodiode array. She was humming in CanTEST’s corner.

It was calibrated to the 10 most commonly prescribed drugs, including ketamine, using lab-based standards.

Chemical X needed to “run a race” against a known sample to compare it to known compounds. It takes approximately 4 minutes to complete the UPLC-PDA test.

Cassie was able to see that the sample looked similar to the ketamine standards. Chemical X ran its race at a similar rate (known as retention time), but it was not absorption of UV radiation.

All that was found was pure and real. It contained neither 2-FDCK nor ketamine.

If in doubt, do more tests

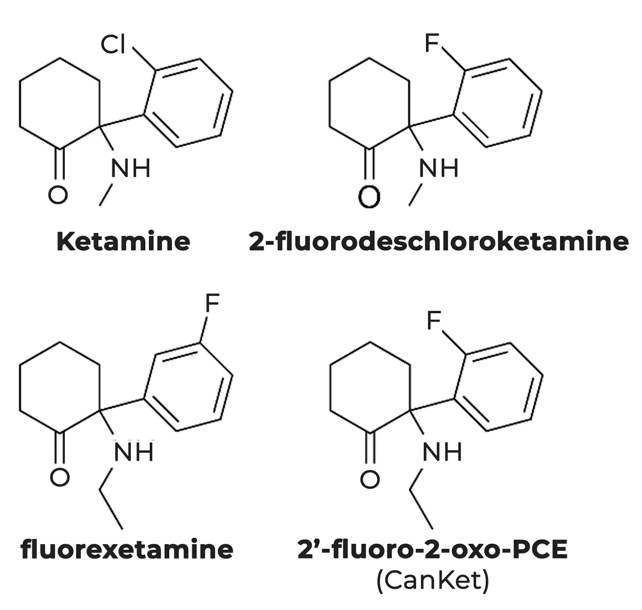

The invaluable drug ketamine can be used in emergency situations and pre-hospital settings. It is also part of a growing group of illegal drugs called “Ketamine”. arylcyclohexamines.

The CanTEST team came up with chemical X as being “ketamine-like” after consulting Mal McLeod (ANU Chemistry Professor).

The person who brought it in was advised the substance was not ketamine, and its identity could not be ascertained – our band of peer workers advised extreme caution in using it.

But that was not the end of the story for analytical chemists – the full inquisition was just beginning.

Next up, chemical X was subjected to a method called gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), meaning the sample was made to ‘run another race’, and was then smashed into pieces to further fingerprint it.

The GC/MS data were closely correlated to a ketamine derivative, known as fluorexetamine, but the presence of an isomer – two compounds with the same molecular formula but arranged differently – could not be ruled out.

It was time for the big guns to come out: A nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum spectrometer (or a chemist’s Book of Runes) is a way to find answers. The language is not easy to learn, but it can lead you to the answers.

After a series multi-dimensional test, the team discovered that there were four hydrogens near each other in the aromatic ring. This meant it couldn’t be fluorexetamine.

Chemical X could only be something called 2′-fluoro-2-oxo-phenylcyclohexylethylamine. This compound was new to them.

From chemical X to “CanKet”

It’s difficult to stress how amazing this piece of work was. We reached out to our contacts at the UN Office of Drug Control and the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction as well as several other well-placed researchers in this area from around the globe.

Nobody had ever seen the compound before.

Our colleagues at ACT Government Analytical Laboratory wrote a letter to their international peers. The global forum for forensic and analytical chemists reviewed the data they had locally collected and provided support information.

From a forensically derived analytical sample, we found one additional report from China. This was described under another name (2FNENDCK). As 2′-fluoro-2-oxo-phenylcyclohexylethylamine is a bit of a mouthful, our team has taken to calling it CanKet, as in ‘Canberra ketamine’.

We are now able, after a thorough chemical analysis, to identify CanKet without any difficulty.

While we still don’t fully understand its effects, understanding its chemical makeup gives us a better picture of how we can deal with it.![]()

David Caldicott, Senior lecturer, Australian National UniversityAnd Malcolm McLeodAssociate Professor Australian National University

This article was republished by The ConversationUnder a Creative Commons License Please read the Original article.