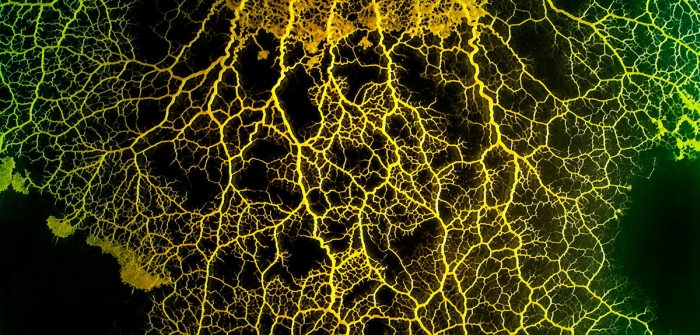

Imagine that you are walking through a forest with your foot rolling over a log. Spreading out on its underside is something moist and yellow – a bit like something you may have sneezed out… if that something was banana-yellow and fanned itself out into elegant fractal branches.

The plasmodium is what you would see. Physarum polycephalumThe many-headed slime mould. It is similar to other slime molds in nature and plays an important ecological function, helping in the decomposition of organic matter in order to recycle it back into the food web.

This strange little organism does not have a brain or nervous system. Its blobby, bright yellow body only has one cell. This slime mold has lived in damp and decaying environments for over a billion of years, almost unchanged.

In the last decade, it has changed how we think of cognition and problem solving.

Audrey Dussutour, a biologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research, said that “I believe it’s exactly the same type of revolution that occurred in the realization that plants can communicate with one another.”

“Even these tiny microbes are capable of learning. It can give you a little humility.”

P. polycephalumIn its natural habitat. (Kay Dee/iNaturalist CC BY -NC)

P. polycephalumIn its natural habitat. (Kay Dee/iNaturalist CC BY -NC)

P. polycephalum – adorably nicknamed “The Blob” by Dussutour – isn’t exactly rare. It can be found in damp, cool, and humid environments such as leaf litter on a forest floor. It is also very peculiar. Although we call it a “mold”, it is actually not fungus. Nor is it animal or plant, but a member of the protist kingdom – a sort of catch-all group for anything that can’t be neatly categorized in the other three kingdoms.

It begins its life with many cells, each one having a single nucleus. The cells then combine to create the PlasmodiumThe vegetative stage of life in which an organism feeds and grows.

This is the form it takes, fanning its way through the veins to find food and explore its surroundings. Although it is still a single cell with millions or billions of nuclei, it is confined to the bright-yellow membrane in cytoplasmic liquid.

A brain is not necessary for cognition

As with all organisms, P. polycephalumIt must be able make informed decisions about its environment. It must be able to find food and avoid danger. It needs to find the best conditions for its reproduction cycle. This is where our yellow friend really shines. P. polycephalumIt doesn’t possess a central nervous. It lacks specialized tissues.

It can even solve difficult puzzles like labyrinth mazesAnd remember novel substances. These were the tasks that we used to believe only animals could do.

“We are talking about cognition that is not based on a brain. But also, without any neurons. The underlying mechanisms and the architecture of how it handles information are completely different to the way your brain works,” Chris Reid, a Macquarie University researcher in Australia, explained ScienceAlert in 2021.

We can see how this fundamentally different system could achieve the same result by giving it the same problems that we have given animals with brains. It’s where it becomes clear that for a lot of these things – that we’ve always thought required a brain or some kind of higher information processing system – that’s not always necessary.”

(David Villa/ScienceImage/CBI/CNRS)

(David Villa/ScienceImage/CBI/CNRS)

P. polycephalumIt is well-known to science. Decades ago, it was, as physicist Hans-Günther Döbereiner of the University of Bremen in Germany explained, the “workhorse of cell biology”. It was easy to copy, keep, then study.

However, our genetic analysis toolkits have allowed us to create organisms such mice or cell lines that can be used for genetic analysis. HeLatook over, P. polycephalumThe wayside.

In 2000, biologist Toshiyuki Nakagaki of RIKEN in Japan brought the little beastie out of retirement – and not for cell biology. His paper, Publié in Nature, bore the title “Maze-solving by an amoeboid organism” – and that’s exactly what P. polycephalum had done.

Nakagaki had placed a piece plasmodium at the end of a maze. This was a reward for food (oats) P. polycephalumLove Oat bacteria) at the other, and watched what happened.

These results were astonishing. It was a strange little organism that could find the fastest path through any maze it encountered.

Reid explained that Reid’s research led to a flood of inquiries into other difficult situations in which slime mold could be tested.

“Virtually all those were surprising in one way or another and the researchers were surprised at how the slime mold performed.” It also revealed some limitations. It was a journey of discovery on how a simple creature can accomplish tasks that were previously thought to be reserved for higher organisms.

It’s full of surprises

Nakagaki recreated Tokyo’s subway system, marking out stations with oats at each node. P. polycephalum It was nearly identically reproduced. – except the slime mold version was more robust to damage, wherein if a link got severed, the rest of the network could carry on.

Another team of researchers discovered that the protist can also efficiently function as a researcher. Problem with the traveling salesmanProgrammers use this exponentially complicated mathematical task to test their algorithms.

allowfullscreen=”allowfullscreen”>

A team of researchers discovered earlier this year that P. polycephalumIt can “remember where it was” Food that was previously foundBased on the structure and arrangement of the veins in the area. Dussutour had previously conducted research with her collaborators, and discovered that slime mold blobs could exist. Remember to learn about substancesThey would communicate any information they didn’t like to other blobs once they fused.

Dussutour shared that she is still stunned by their complexity because they surprise you in experiments, and they will never do exactly the same thing you do.”

One instance was when her team was trying out a growth medium for mammal cells. They wanted to see how slime reacts.

“It Hated it. It began to create this strange three-dimensional structure in order to escape and go on the lead. It was like, “Oh my god, this organism!”

A processing network

It is technically a single-celled organism. P. polycephalumIt is a network that exhibits collective behavior. Each component of the slime mould operates independently, sharing information with its neighbors without centralized processing.

Reid suggested that neurons in a human brain would be an analogy. “You have this one brain that’s composed of lots of neurons – it’s the same for the slime mold.”

Physarym polycephalum “The blob”,

Network emergence

Oscillation waves#blob pic.twitter.com/kJUhH0w05a— Audrey Dussutour (@Docteur_Drey) April 3, 2021

This brain analogy is very intriguing, and I’m sure it will be used again. P. polycephalumIt has been compared with a network of neurons. Both the topology and structure in brain networks and slime molds blobs is very similar. Both systems also exhibit oscillations.

Although it is not clear exactly how information is transmitted and shared in slime molds, we know that P. polycephalumThe cytoplasmic fluid is pushed from one section to the next by the contraction of the veins. Oscillations in the fluid appear to be related to external stimuli.

“It’s thought that these oscillations convey information, process information, by the way they interact and actually produce the behavior at the same time,” Döbereiner told ScienceAlert.

“If your network is comprised of PhysarumWhen it comes in contact with sugar, its oscillation pattern changes and it oscillates faster. The organism changes its oscillation patterns faster and flows in the same direction as the food.

He and his coworkers Published a paperIn 2021, these oscillations were shown to be very similar to oscillations in a brain. However, they are hydrodynamic rather than electrical.

“What’s relevant is not so much what oscillates and how the information is transported,” he explains, “but that it oscillates and that a topology is relevant – is one neuron connected to 100 neurons or just to two; is a neuron connected just to its neighbors or is it connected to another neuron very far away.”

P. polycephalumA life-sized replica of a human skull is used to help you grow. (Andrew Adamatzky, Artifical life, 2015)

P. polycephalumA life-sized replica of a human skull is used to help you grow. (Andrew Adamatzky, Artifical life, 2015)

Definition of cognition

No matter how exciting its adventures might seem, any researcher who works with it will tell the truth. P. polycephalumIt is not a brain by itself. As far as we know, it is incapable of abstract reasoning or higher-level processing.

The idea of a brain is not likely, despite how intriguing it may seem. It has been able to evolve into a brain for a billion years, but it is not showing any signs of doing so. Science fiction writers who like the idea can take it up.

Slime mold’s overall biology is very simple. Because of this, slime mold is changing how we approach problem-solving.

Like all organisms, it requires food, navigation, and a safe environment to grow and reproduce. These problems can be difficult to understand, but they are still important. P. polycephalumThey can be solved with the extremely limited cognitive architecture. It does it in its own unique way and with its limitations, Reid stated, but that’s one of the great things about this system.

In a sense, it leaves us with an organism – a wet, slimy, damp-loving blob – whose cognition is fundamentally different from our own. This can help us find new solutions to our own problems, much like the Tokyo subway.

Reid stated that it was teaching them about intelligence’s nature, challenging certain views and essentially broadening their concept.

“It forces us to question these long-held anthropocentric beliefs about ourselves as unique and capable of so many more than other creatures.

A version of this article first appeared in June 2021.