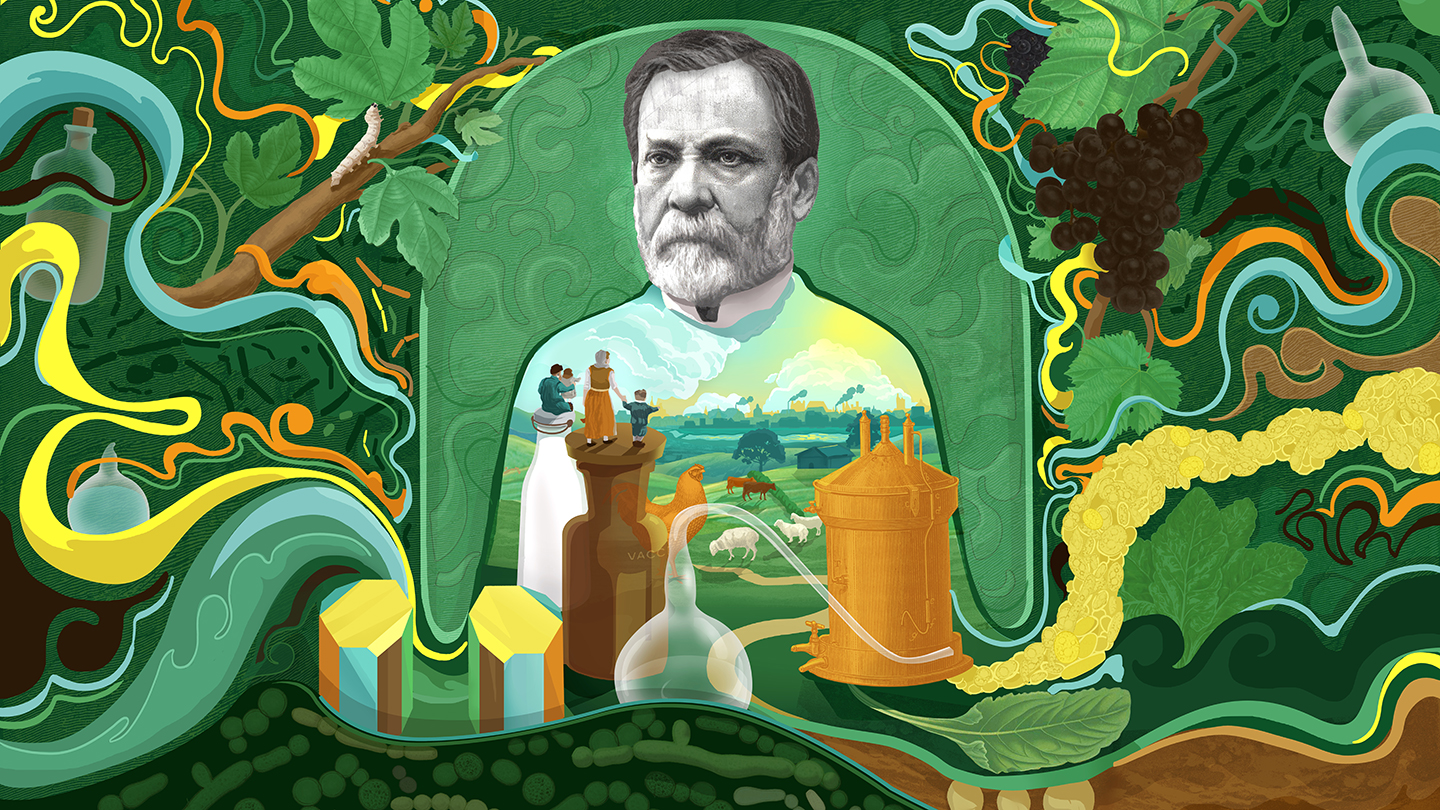

In many ways, great scientists are immortalized.

Some through names for obscure units of measurement (à la Hertz, Faraday and Curie). Others may be found in elements on a periodic tableMendeleev, Seaborg, Bohr, and many others. A few become household names symbolizing genius — like Newton in centuries pastToday, and everywhere else. Einstein. However, only one name has been mentioned on millions and billions of cartons of milk: Louis Pasteur, French biologist, chemist, and evangelist in experimental science.

Pasteur was Born 200 years agoThis December, the bicentennial celebration of the greatest scientist birthday ever Charles Darwin’s in 2009. Pasteur was second to Darwin in the list of exceptional bioscientists of the 19th Century.

Pasteur did more than make milk safe to drink. He also saved the beer and wine industries. Pasteur created the germ theory of disease and saved the French silkworm population. He also transformed smallpox vaccination into a strategy to treat and prevent human diseases. He created microbiology and the foundations of immunology.

If he had been alive in 1901 when Nobel Prizes first became available, he would have received one each year for the past decade. There is no scientist who has demonstrated science’s benefit for humanity more clearly than he.

However, he was not exactly a saint. A Pasteur biographer, Hilaire Cuny, called him “a mass of contradictions.” Pasteur was ambitious and opportunistic, sometimes arrogant and narrow-minded, immodest, undiplomatic and uncompromising. He was aggressive and pugnacious in the scientific controversies that he participated in, which were many. He was not one to be taken lightly and was often blunt in his replies. He was demanding, controlling, and distant to his lab assistants. Despite his innovative spirit in science and in social and political matters, he was conformist, and deferential towards authority.

He was an unstoppable worker, motivated by humankind, faithful and honest, and he was also a great friend. He was dedicated to truth and science.

How Pasteur developed pasteurization

Pasteur didn’t excel in school as a teenager. His interest was in art and not science. Pasteur did however have exceptional drawing and painting skills. But in light of career considerations (his father wanted him to be a scholar), Pasteur abandoned art for science and so applied to the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in Paris for advanced education. Pasteur was able to get admission by finishing 15th in the entrance exam. Pasteur, however, did not find him to be a good enough candidate. He spent another year on further studies emphasizing physical sciences and then took the École Normale exam again, finishing fourth. This was enough to get him into the school in 1843. He received his doctoral degree in physics and chemical chemistry there in 1847.

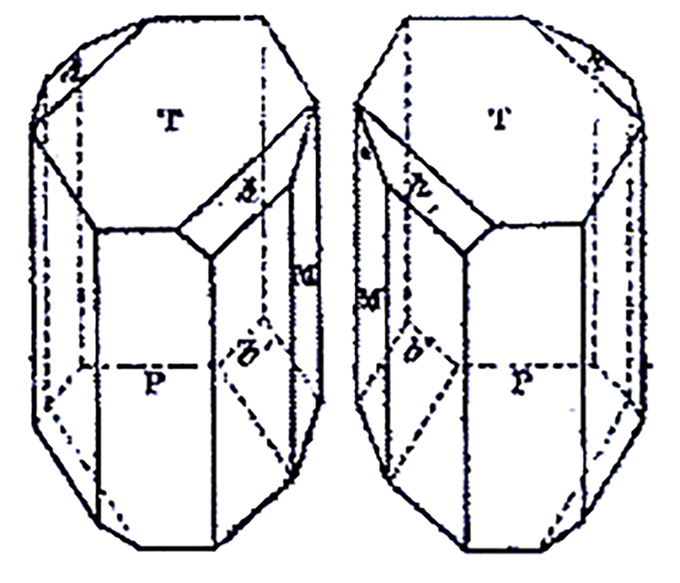

Among his special interests at the École Normale was crystallography. He was particularly drawn to tartaric acid research. It’s a chemical found in grapes responsible for tartar, a potassium compound that collects on the surfaces of wine vats. Scientists had recently discovered that tartaric acid possesses the intriguing power of twisting light — that is, rotating the orientation of light waves’ vibrations. When light is polarized, it aligns in a single plane. This can be done by passing it through certain filters, crystals, or sunglasses. A tartaric acid solution is used to make light travel along one plane.

Surprisingly, a second acid (paratartaric or racemic), which had the exact same chemical formula as tartaric, failed to turn light on at all. Pasteur found that to be suspicious. Pasteur began an extensive study of the crystals formed from the two acids. He found that racemic acids crystals could be divided into two mirror-image shapes. This is similar to pairs of left-handed and right-handed gloves. Tartaric acid crystals on the other side had identical shapes to the gloves that were all right-handed.

Pasteur concluded that crystal asymmetry was due to the asymmetric arrangement in the atoms within the constituent molecules. Tartaric acid twisted light because of the asymmetry of its molecules, while in racemic acid, the two opposite shapes canceled out each other’s twisting effects.

Pasteur based his entire career on this discovery. Pasteur’s research on tartaric acid, wine, and other microbes led to some profound insights about the link between human disease and microbes. Most experts believed that fermentation was a nonbiological chemical process. Although yeast is a key ingredient in fermentation fluid, it was believed to be a dead chemical acting as a catalyst. Pasteur’s experiments showed yeast to be alive, a peculiar kind of “small plant” (now known to be a fungus) that caused fermentation by biological activity.

Pasteur proved that yeast can acquire oxygen from sugar in the absence of air and convert the sugar into alcohol. “Fermentation by yeast,” he wrote, is “the direct consequence of the processes of nutrition,” a property of a “minute cellular plant … performing its respiratory functions.” Or more succinctly, he proclaimed that “fermentation … is life without air.” (Later scientists found that yeast accomplished fermentation by emitting enzymes that catalyzed the reaction.)

Pasteur noticed that other microorganisms could cause fermentation to go wrong, which could threaten the viability and sustainability of French winemaking as well as beer brewing. Pasteur devised a heating technique that could eliminate bad microorganisms, while still maintaining the quality of the beverage. This method, called “pasteurization,” was later applied to milk, eliminating the threat of illness from drinking milk contaminated by virulent microorganisms. In the 20th century, pasteurization was a standard practice in public health.

Pasteur summarized his research on microbial biology in a paper published in 1857, incorporating additional insights from studies of other types of fermentation. “This paper can truly be regarded as the beginning of scientific microbiology,” wrote the distinguished microbiologist René Dubos, who called it “one of the most important landmarks of biochemical and biological sciences.”

The germ theory is the foundation of all disease.

Pasteur’s investigations of the growth of microorganisms in fermentation collided with another prominent scientific issue: the possibility of spontaneous generation of life. Even among scientists, the belief that microbial life could self-generate under the right conditions (spoiled food, for instance) is common opinion. Demonstrations by an Italian scientist from the 17th Century Francesco Redi challenged this beliefHowever, the case against spontaneous generation is not strong.

Pasteur conducted a series experiments in the early 1860s that should have made it clear that spontaneous generation under current conditions was an illusion. However, Pasteur was still confronted by critics like Charles-Philippe Robin in France, who he responded verbally. “We trust that the day will come when M. Robin will … acknowledge that he has been in error on the subject of the doctrine of spontaneous generation, which he continues to affirm, without adducing any direct proofs in support of it,” Pasteur remarked.

Pasteur’s work on spontaneous generation was what led to the creation of the germ theory.

People have known for centuries that certain diseases can be passed from one person to another through close contact. It was beyond scientific capability to figure out how this happened. Pasteur, who had already identified the role of germs during fermentation, realized that what makes wine go bad could also cause harm to human health.

After disproving spontaneous generation, he realized that there must exist “transmissible, contagious, infectious diseases of which the cause lies essentially and solely in the presence of microscopic organisms.” For some diseases, at least, it was necessary to abandon “the idea of … an infectious element suddenly originating in the bodies of men or animals.” Opinions to the contrary, he wrote, gave rise “to the gratuitous hypothesis of spontaneous generation” and were “fatal to medical progress.”

In response to declining French silk production due to diseases that afflicted silkworms, his first attempt at applying the germ theory was made in the late 1860s. After success in tackling the silkworms’ maladies, he turned to anthrax, a terrible illness for cattle and humans alike. Many medical experts had long suspected that some form of bacteria caused anthrax, but it was Pasteur’s series of experiments that isolated the responsible microorganism, verifying the germ theory beyond doubt. (Similar work by Robert Koch in Germany(Also, additional confirmation was provided.)

Understanding anthrax’s cause led to the search for a way to prevent it. In this case, a fortuitous delay in Pasteur’s experiments with cholera in chickens produced a fortunate surprise. In the spring of 1879 he had planned to inject chickens with cholera bacteria he had cultured, but he didn’t get around to it until after his summer vacation. In the fall, he accidentally injected his chickens and they died. Pasteur made a fresh bacterial culture, and brought in another batch of chickens.

The fresh bacteria was given to both the new and previous batches of chickens. However, almost all the original chickens survived. Pasteur soon realized that the original culture had lost its potency and was no longer able to cause disease. However, the new, stronger culture didn’t harm the chickens that were previously exposed to it. “These animals have been vaccinated,” he declared.

Vaccination was invented in the eighteenth century, but it wasn’t until 1980 that it became a reality. Edward Jenner, a British doctorPeople were protected from smallpox when they were first exposed to cowpox (a similar disease that is acquired from cows). (Vaccination comes from cowpox’s medical name, vaccinia, from vaccaLatin for cow. Pasteur realized that the chickens surprisingly displayed a similar instance of vaccination because he was aware of Jenner’s discovery. “Chance favors the prepared mind,” Pasteur was famous for saying.

Because of his work on the germ theory of disease, Pasteur’s mind was prepared to grasp the key role of microbes in the prevention of smallpox, something Jenner could not have known. Pasteur immediately realized that the idea of smallpox vaccination could be extended to other diseases. “Instead of depending on the chance finding of naturally occurring immunizing agents, as cowpox was for smallpox,” Dubos observed, “it should be possible to produce vaccines at will in the laboratory.”

Pasteur cultivated the anthrax microbe, and then weakened it to be tested in farm animals. The success of such tests confirmed the validity of the germ theory and gave rise to new medical practices.

Pasteur was later confronted with a more complex microscopic foe: the virus that causes Rabies. He had begun intense experiments on rabies, a horrifying disease that’s almost always fatal, caused usually by the bites of rabid dogs or other animals. He failed to discover any bacteria that could cause rabies in his experiments, and realized it was likely to be caused by an agent too small for him to see through his microscope. He couldn’t grow cultures in lab dishes from what he couldn’t see. So instead he decided to grow the disease-causing agent in living tissue — the spinal cords of rabbits. He used the spinal cords from infected rabbits as a vaccine to treat other animals.

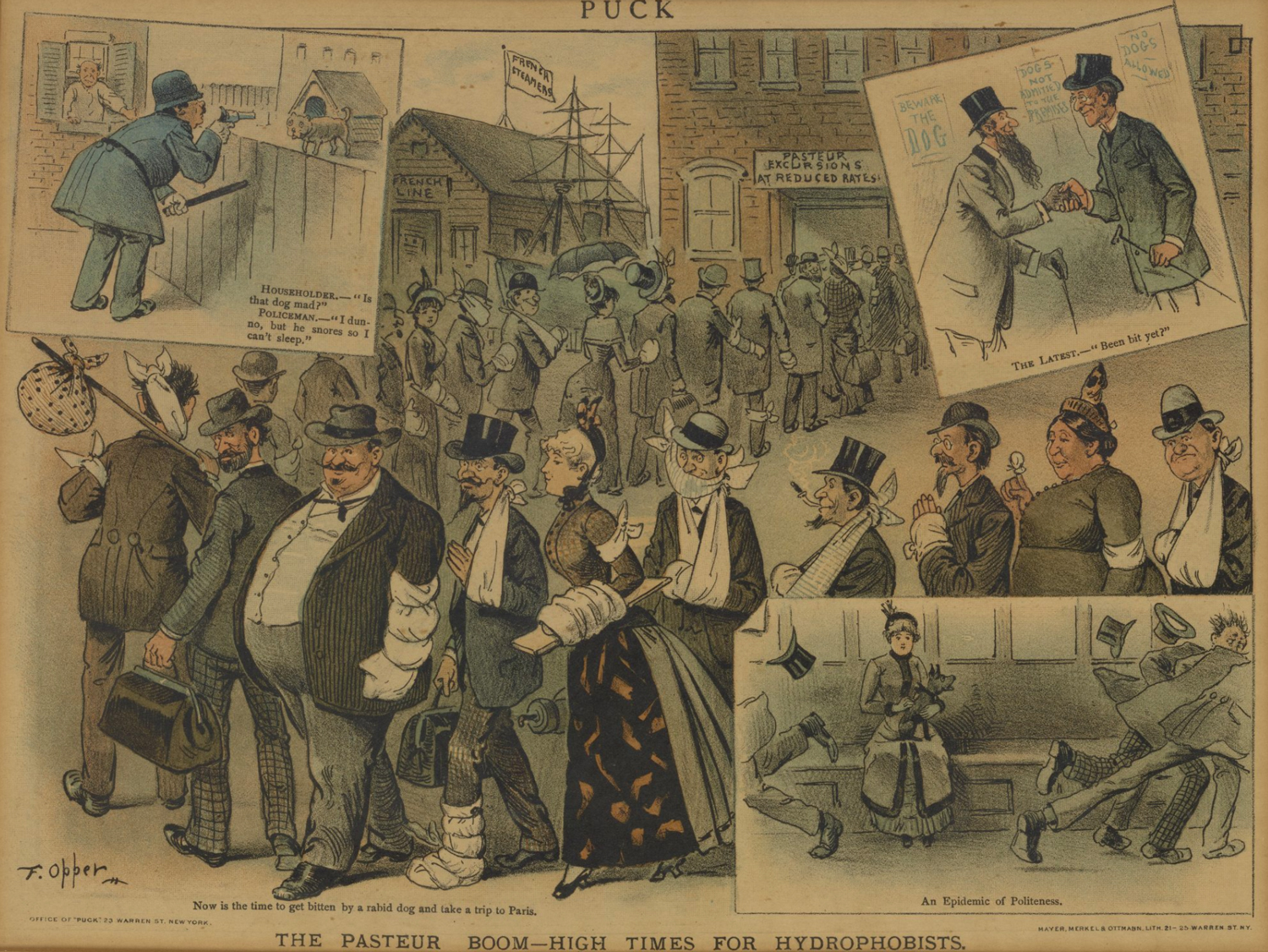

Pasteur resisted the temptation to test his rabies vaccine on humans. Pasteur still agreed to administer the vaccine in 1885 to a 9 year-old boy who was badly bitten by a vicious dog. The boy was fully recovered after a series of injections. The rabies vaccine was soon requested by more people. By the beginning of the next year, over 300 rabies patients had been vaccinated and had survived. There was only one death.

Pasteur is a hero who was widely hailed. However, some doctors hated Pasteur because they considered him an unqualified interloper in medicine. Vaccine opponents claimed Pasteur’s vaccine was not tested and might cause death. But of course, critics had also rejected Pasteur’s view of fermentation, the germ theory of disease and his disproof of spontaneous generation.

Pasteur stood firm and won the battle (although he didn’t always win every time). His spirit and achievements inspired 20th-century scientists who developed vaccines for over a dozen of the most deadly diseases. Still more diseases succumbed to antibiotics, following the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming — who declared, “Without Pasteur I would have been nothing.”

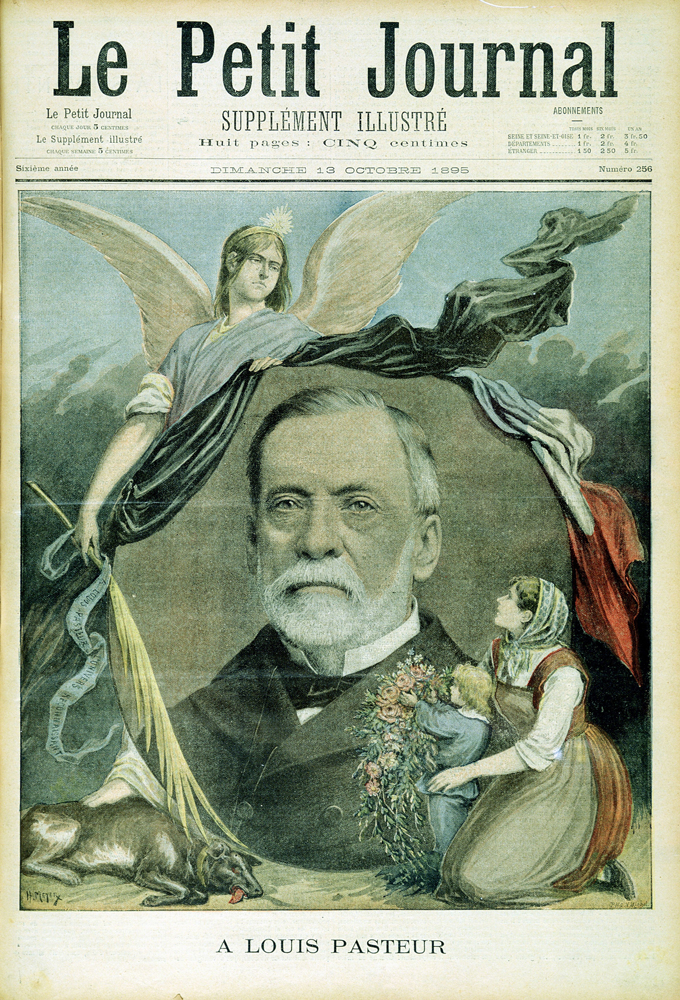

Even in Pasteur’s own lifetime, thanks to his defeat of rabies, his public reputation was that of a genius.

Pasteur’s scientific legacy

Pasteur was the opposite of Einstein as geniuses go. Einstein dreamed of falling off a ladder or riding on a light beam to inspire his theories. Pasteur stayed true to his experiments. Pasteur was a stickler for experiments. He often started his experiments with a suspect result in mind but was meticulous in verifying the conclusions. Preconceived ideas, he said, can guide the experimenter’s interrogation of nature but must be abandoned in light of contrary evidence. “The greatest derangement of the mind,” he declared, “is to believe in something because one wishes it to be so.”

Pasteur believed his view was correct and continued to do experiments with different interpretations.

“If Pasteur was a genius, it was not through ethereal subtlety of mind,” wrote Pasteur scholar Gerald Geison. Rather, he exhibited “clear-headedness, extraordinary experimental skill and tenacity — almost obstinacy — of purpose.”

His determination or perseverance helped him to overcome many personal tragedies such as the deaths three of his daughters in 1859-1865, and 1866. In 1868, he was paralysed on his left side from a cerebral hemorhage. He continued his investigations without any limitations.

“Whatever the circumstances in which he had to work, he never submitted to them, but instead molded them to the demands of his imagination and his will,” Dubos wrote. “He was probably the most dedicated servant that science ever had.”

Pasteur was a staunch supporter of science and the scientific method until the end, highlighting the importance of experimental science to society. Laboratories are “sacred institutions,” he asserted. “Demand that they be multiplied and adorned; they are the temples of wealth and of the future.”

Pasteur, three years before his death in 1895 extolled science’s value and expressed his hope that science would triumph. In an address, delivered for him by his son, at a ceremony at the Sorbonne in Paris, he expressed his “invincible belief … that science and peace will triumph over ignorance and war, that nations will unite, not to destroy, but to build, and that the future will belong to those who will have done most for suffering humanity.”

Two hundred years later, he was born.As intractable as the microbes that continue their threat to public health, ignorance and war are perniciously prevalent. COVID-19 virusThis is the most recent example. The risks of COVID-19 have been substantially reduced by vaccines. This extends the list of successful vaccines that have not only tamed smallpox, rabies, and also vaccinated. Polio, measles, and many other once-deadly diseases.

But despite vaccines saving countless millions of people’s lives, certain politicians and scientists ignore overwhelming evidence. continue to condemn vaccinesThey are more dangerous than the diseases that they prevent. While some vaccines may cause adverse reactions that can be fatal, only a handful of thousands of them are known to cause such severe side effects. However, avoiding vaccines is like refusing food because people choke on sandwiches.

Today, Pasteur would be vilified just as he was in his own time, probably by some people who don’t even realize that they can safely drink milk because of him. We don’t know what Pasteur would tell these people. But it’s certain that he would stand up for truth and science, and would be damn sure to tell everybody to get vaccinated.