One hundred years ago, archaeologist Howard Carter stumbled across the tomb of ancient Egypt’s King Tutankhamun. Carter’s life was never the same. Neither was the young pharaoh’s afterlife.

Newspapers around the world immediately ran stories about Carter’s discovery of a long-lost pharaoh’s grave and the wonders it might contain, propelling the abrasive Englishman to worldwide acclaim. A Boy kingThe most well-known pharaoh was once lost in ancient obscuritySN: 12/18/76).

It all started on November 4, 1922, when excavators led by Carter discovered a step cut into the valley floor of a largely unexplored part of Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. The team discovered stairs that led to a door by November 23. A hieroglyphic seal on the door identified what lay beyond: King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Tutankhamun, who was just 10 years old, assumed power in 1334 B.C. His reign lasted almost a decade before his death. Tutankhamun, a minor Egyptian pharaoh, is one of few whose lavishly decorated burial site was found intact.

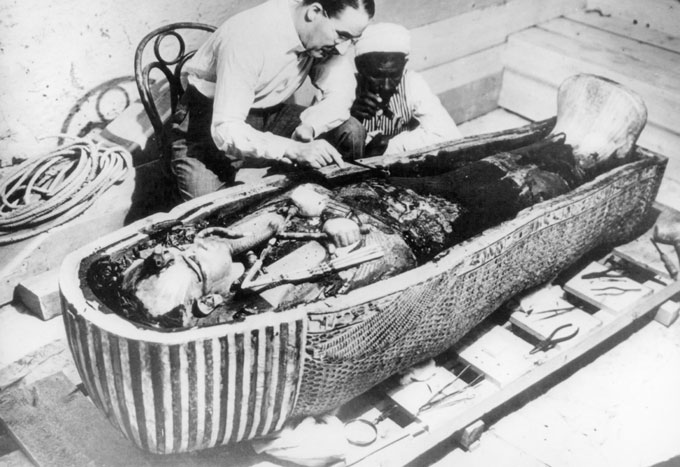

An unusually meticulous excavator for his time, Carter organized a 10-year project to document, conserve and remove more than 6,000 items from Tutankhamun’s four-chambered tomb. While some objects, like Tut’s gold burial mask, are now iconic, many have been in storage and out of sight for decades. But that’s about to change. About 5,400 of Tutankhamun’s well-preserved tomb furnishings are slated to soon go on display when Grand Egyptian MuseumThe Pyramids of Giza are located near the entrance to.

“The [Tut] burial hoard is something very unique,” Shirin Frangoul-Brückner, managing director of Atelier Brückner in Stuttgart, Germany, the firm that designed the museum’s Tutankhamun Gallery, said in an interview released by her company. The exhibit will include, among others, the gold burial masque, musical instruments and hunting equipment, as well as jewelry and six chariots.

Even as more of Tut’s story is poised to come to light, here are four things to know on the 100th anniversary of his tomb’s discovery.

1. Tut may not be frail.

Tutankhamun was a young, fragile man who could only walk on one foot. Researchers suspect that Tutankhamun’s weak immune system may have contributed to his early death.

But “recent research suggests it’s wrong to portray Tut as a fragile pharaoh,” says Egyptologist and mummy researcher Bob Brier, who is an expert on King Tut. His new book Tutankhamun’s Tomb that Changed the World chronicles how 100 years of research have shaped both Tut’s story and archaeology itself.

Clues from Tutankhamun’s mummy and tomb items boost his physical standing, says Brier, of Long Island University in Brookville, N.Y. Perhaps the young pharaoh even participated in war.

Brier says that Tutankhamun buried military chariots and leather armor with his archery equipment. This shows that he was a hunter and warrior. Inscribed blocks from Tutankhamun’s temple, which were reused in later building projects before researchers identified them, portray the pharaoh leading charioteers in undated battles.

Brier suggests that more blocks may contain battle scenes marked by dates. This would indicate that Tutankhamun was involved in these conflicts. Pharaohs usually kept dates of actual battles in their temples. However, inscribed scenes could have exaggerated the heroism.

The frail story line has been built in part on the potential discovery of a deformity in Tut’s left foot, along with 130 walking sticks found in his tomb. Brier states that ancient Egyptian officials often wore walking sticks to signify authority and not infirmity. And researchers’ opinions vary about whether images of Tut’s bones reveal serious deformities.

The 1960s X-rays of the mummy recovered from Egypt show no evidence of a limp. CT images taken in 2005 by Egyptologist Zahi Hawass (ex-Minister of Antiquities Egypt), did not show any signs of a limp.

A 2009 reexamination by the same researchers of CT images revealed that Tutankhamun suffered from a left-foot defect, which is usually associated with walking on one side or the other of the feet. The team’s radiologist, Sahar Saleem of Egypt’s Cairo University, says the CT images show that Tutankhamun experienced a mild left clubfoot, bone tissue death at the ends of two long bones that connect to the second and third left toes and a missing bone in the second left toe.

Those foot problems would have “caused the king pain when he walked or pressed his weight on his foot, and the clubfoot must have caused limping,” Saleem says. So a labored gait, rather than an appeal to royal authority, could explain the many walking sticks placed in Tutankhamun’s tomb, she says.

Brier however doubts this scenario. Tutankhamun’s legs appear to be symmetrical in the CT images, he says, indicating that any left foot deformity was too mild to cause the pharaoh regularly to put excess weight on his right side while walking.

The discovery and analysis of the mummy of the boy king made it clear that he died at the age of 19, just as he was about to become an adult. Yet Tut’s cause of death still proves elusive.

In a 2010 analysis of DNA extracted from the pharaoh’s mummy, Hawass and colleagues contended that As well as the tissue-destroying disease bone disorder, malaria cited by Saleem from the CT images, hastened Tutankhamun’s death. Brier is not the only one to disagree. The mystery of ancient DNA could be solved using new powerful tools for extracting and testing the genetic material from mummies.

2. Tut’s initial obscurity led to his fame.

After Tutankhamun’s death, ancient Egyptian officials did their best to erase historical references to him. His reign was rubbed out because his father, Akhenaten, was a “heretic king” who alienated his own people by banishing the worship of all Egyptian gods save for one.

“Akhenaten is the first monotheist recorded in history,” Brier says. Ordinary Egyptians, who previously worshipped hundreds of gods, suddenly found that Aten was all they needed.

Meeting intense resistance to his banning of cherished religious practices, Akhenaten — who named himself after Aten — moved to an isolated city, Amarna, where he lived with his wife Nefertiti, six girls, one boy and around 20,000 followers. Residents of the desert outpost returned home to their homes after Akhenaten’s death. Egyptians returned to their traditional religion. Akhenaten’s son, Tutankhaten — also originally named after Aten — became king, and his name was changed to Tutankhamun in honor of Amun, the most powerful of the Egyptian gods at the time.

Later, the pharaohs deleted from their written records any mentions Akhenaten and Tutankhamun. Tut’s tomb was treated just as dismissively. Huts of craftsmen working on the tomb of King Ramses VI nearly 200 years after Tut’s death were built over the stairway leading down to Tutankhamun’s nearby, far smaller tomb. The site was littered by limestone chips.

Carter found the huts and left them there until Carter arrived. While Carter found evidence that the boy king’s tomb had been entered twice after it was sealed, whoever had broken in took no major objects.

“Tutankhamun’s ignominy and insignificance saved him” from tomb robbers, says UCLA Egyptologist Kara Cooney.

3. Tut’s tomb was a rushed job.

The tombs of the Pharaohs were usually built over many decades. They had numerous rooms that could hold treasures or extravagant coffins. Egyptian customs required that the mummified body be placed in a tomb 70 days after it died. Brier suggests that this time allowed the mummy to dry sufficiently and retain enough moisture to allow the arms to be folded across the body in a coffin.

Tutankhamun’s premature death meant that he didn’t have the time to prepare his tomb. The 70-day burial custom left craftsmen with little time to finish important tomb items. Some of them took more than a year to make. Those objects include a carved stone sarcophagus that encased three nested coffins, four shrines, hundreds of servant statues, a gold mask, chariots, jewelry, beds, chairs and an alabaster chest that contained four miniature gold coffins for Tutankhamun’s internal organs removed during mummification.

Evidence points to workers repurposing many objects from other people’s tombs for Tutankhamun. But time was running out.

Take a look at the sarcophagus. Two of the four goddesses in the stone container have no fully carved jewelry. Workers painted the missing pieces of jewelry. Unfinished pillars carved on the sarcophagus were also found.

Tutankhamun’s granite sarcophagus lid, a mismatch for the quartzite bottom, provides another clue to workers’ frenzied efforts. Brier says that something must have happened to the original quartzite cover, so workers made a new lid out of granite and painted it to look similar to quartzite.

The new lid was repaired to show that it split in half during carving. “Tutankhamun was buried with a cracked, mismatched sarcophagus lid,” Brier says.

Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus may originally have been made for Smenkare, a mysterious individual who some researchers identify as the boy king’s half brother. Little is known about Smenkare, who possibly reigned for about a year after Akhenaten’s death, just before Tutankhamun, Brier says. But Smenkare’s tomb has not been found, leaving the sarcophagus puzzle unsolved.

Objects including the young king’s throne, three nested coffins and the shrine and tiny coffins for his internal organs also contain evidence of having originally belonged to someone else before being modified for reuse, says Harvard University archaeologist Peter Der Manuelian.

Even Tutankhamun’s tomb may not be what it appears. Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves of the University of Arizona Egyptian Expedition in Tucson has argued since 2015 that the boy king’s burial place was intended for Nefertiti. He argues that Nefertiti briefly succeeded Akhenaten as Egypt’s ruler and was the one given the title Smenkare.

No one has found Nefertiti’s tomb yet. But Reeves predicts that one wall of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber blocks access to a larger tomb where Nefertiti lies. Painted scenes and writing on that wall depict Tutankhamun performing a ritual on Nefertiti’s mummy, he asserts. And the gridded structure of those paintings was used by Egyptian artists years before Tutankhamun’s burial but not at the time of his interment.

But four of five remote sensing studies conducted inside Tutankhamun’s tomb have found no evidence of a hidden tomb. Like Smenkare and Nefertiti, the mystery of Nefertiti remains.

4. Tut’s tomb changed archaeology and the antiquities trade.

Carter’s stunning discovery occurred as Egyptians were protesting British colonial rule and helped fuel that movement. Carter and Lord Carnarvon, a British aristocrat, were adamant that Carter’s exclusive newspaper coverage on the excavation was his. The TimesLondon. Things got so bad that Egypt’s government locked Carter out of the tomb for nearly a year, starting in early 1924.

Egyptian nationalists wanted political independence — and an end to decades of foreign adventurers bringing ancient Egyptian finds back to their home countries. Tutankhamun’s resurrected tomb pushed Egyptian authorities toward enacting laws and policies that helped to end the British colonial state and reduce the flow of antiquities out of Egypt, Brier says, though it took decades. 1953 saw Egypt become an independent nation. An Egyptian law of 1983 prohibited the exportation of antiquities from Egypt. However, those that were removed prior to 1983 can still be legally owned and sold through auction houses.

In 1922, however, Carter and Lord Carnarvon regarded many objects in Tutankhamun’s tomb as theirs for the taking, Brier says. That was the way that Valley of the Kings excavations had worked for the previous 50 years, in a system that divided finds equally between Cairo’s Egyptian Museum and an expedition’s home institution. Common was the taking of personal mementos.

Evidence of Carter’s casual pocketing of various artifacts while painstakingly clearing the boy king’s tomb continues to emerge. “Carter didn’t sell what he took,” Brier says. “But he felt he had a right to take certain items as the tomb’s excavator.”

Recently recovered letters of English Egyptologist Alan Gardiner from the 1930s, described by Brier in his book, recount how Carter gave Gardiner several items from Tutankhamun’s tomb, including an ornament used as a food offering for the dead. French Egyptologist Marc Gabolde of Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3 University has tracked down beads, jewelry, a headdress fragment and other items taken from Tutankhamun’s tomb by Carter and Carnarvon.

Yet it is undeniable that one of Tutankhamun’s greatest legacies, thanks to Carter, is the benchmark the excavation of his tomb set for future excavations, Brier says. Carter began his career in art, replicating the images of Egyptian tomb walls for excavators. Flinders Petrie, an English Egyptologist, helped Carter learn excavation techniques. Carter elevated tomb documentation to a whole new level by assembling a crack team that included a photographer and conservator, two draftsmen as well as an engineer, and an authority on ancient Egyptian writing.

Their decade-long efforts also led to the creation of the new Tutankhamun museum at the Grand Egyptian Museum. Now, not only museum visitors but also a new generation of researchers will have unprecedented access to the pharaoh’s tomb trove.

“Most of Tutankhamun’s [tomb] objects have been given little if any study beyond what Carter was able to do,” says UCLA’s Cooney.

That won’t be true for much longer, as the most famous tomb in the Valley of the Kings enters the next stage of its public and scientific afterlife.