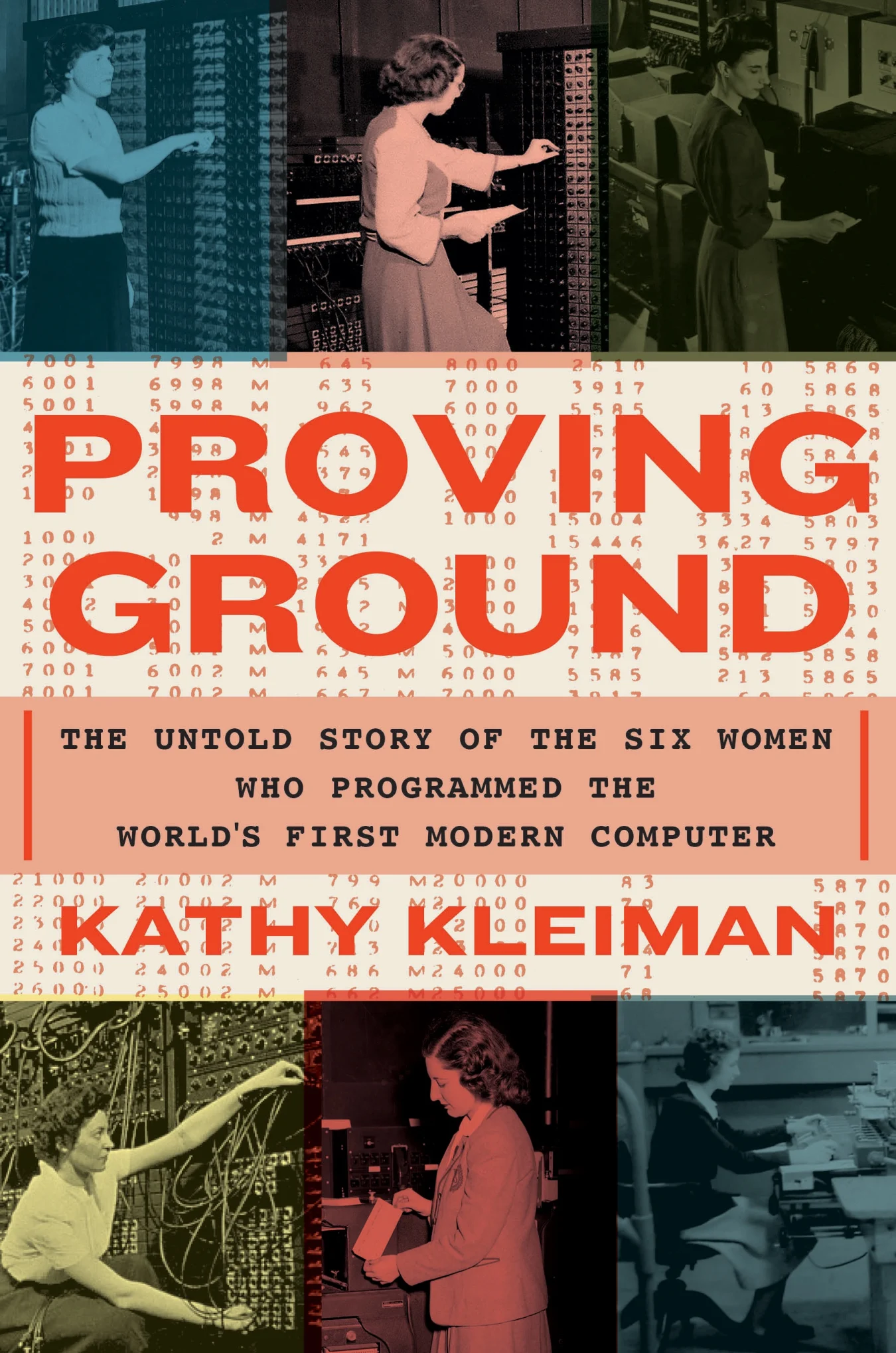

AFter Mary Sears, along with her team, had revolutionized oceanographyBut before Katherine G. Johnson and Dorothy Vaughan, Mary JacksonJohn Glenn’s orbit was made possible by a team of women programmers for the US government. Their task was to train ENIAC (the world’s first modern computer) to do more than simply calculate artillery trajectory paths. Though successful — and without the aid of a guide or manual no less — their names and deeds were lost to the annals of history, until author Kathy Kleiman, through a Herculean research effort of her own, brought their stories to light in Proving Ground: The Untold Story of the Six Women Who Programmed the World’s First Modern Computer.

Grand Central Publishing

Excerpted From the Book Proving Ground: The Untold Story of the Six Women Who Programmed the World’s First Modern ComputerKathy Kleiman Copyright © 2022 by First Byte Productions, LLC. Grand Central Publishing has granted permission for this reprint. All rights reserved.

Demonstration day, February 15, 1946

As people arrived by trolley and train, the Moore School was there. John and Pres, as well as the engineers and deans and professors of the university, wore their best suits and Army officers were in dress uniform with their medals gleaming. The six women wore the best professional skirt suits or dresses.

Kay and Fran were the front doors to the Moore School. They were welcoming the technologists and scientists from Boston as they arrived. They requested that everyone hang their winter coats on the portable racks left by Moore School staff nearby. They then directed them down the hall to the ENIAC area.

Fran and Kay ran back to the ENIAC area just before 11:00 am when the demonstration began.

Everything was available as they made their way to the back of the room. There was plenty of space at the front of the ENIAC U for speakers and a few rows and chairs. ENIAC team members and invited guests had plenty of room. Marlyn and Betty stood in the back, while Jean and Jean smiled at one another. Their big moment was just about to start. Ruth remained outside and pointed late arrivals in the correct direction.

The room was packed and was filled with an air of anticipation and wonder as people saw ENIAC for the first time.

A few introductions were made to the participants of Demonstration Day. Major General Barnes started with the BRL officers and Moore School deans and then presented John and Pres as the co-inventors. Arthur appeared at the front of the room to introduce himself as the master de ceremonies for the ENIAC event. He would run five programs, all using the remote control box he held in his hand.

The first program was an addition. Arthur hit one the but-tons, and the ENIAC whirled back to life. Then, he did a multiplication. His experts knew that ENIAC could calculate it much faster than any other machine. Next, he ran the table with squares and cubes. Then he ran sines as well as cosines. Demonstration Day had been the same as two weeks before, but for this sophisticated audience the presentation was quite boring.

Arthur was only getting started, and the drama was about begin. He said that he would now run a ballistics trajectory on ENIAC three times.

He pressed the button once and ran it. The trajectory “ran beautifully,” Betty remembered. Arthur ran the same trajectory again but without the printing of punched cards. It ran much faster. The actual speed of things was actually slowened by the punched cards.

Arthur then pointed everyone at the tiny lights that were at the tops of the accumulators. He encouraged his audience to pay close attention to them over the next few minutes. Pres nodded and turned the lights off. The status lights for the ENIAC units were dimmed in the black room. All else was in darkness.

Arthur lit up the ENIAC with a simple click. The ENIAC lit up for twenty seconds. Those watching the accumulators closely saw the 100 tiny lights twinkle as they moved in a flash, first going up as the missile ascended to the sky, and then going down as it sped back to earth, the lights forever changing and twinkling. Those twenty seconds felt both inexorable and immediate.

Then the ENIAC finished, and darkness filled the room again. Pres and Arthur waited for a while, then Pres turned the lights on and Arthur announced that ENIAC had completed its trajectory faster than it would have taken a missile to leave artillery’s muzzle and hit its target. “Everybody gasped.”

It took less than twenty seconds. The audience was made up of engineers, scientists, mathematicians, and technologists. They knew how long it took to calculate a differential equation manually. ENIAC calculated the work of a week in just two hours and a half. They understood that the world had changed.

Everyone in the room was beaming after Climax was completed. The Army officers knew their risk had paid off. Their hardware was a success, according to the ENIAC engineers. The Moore School deans understood that they didn’t have to worry about being embarrassed. ENIAC Programmers knew that their plan had worked. It had taken years of hard work, effort and creativity to bring about twenty seconds of pure innovation.

Some would later call this moment the birth of the “Electronic Computing Revolution.” Others would soon call it the birth of the Information Age. In those precious twenty seconds, nobody would look again at the Mark I electromechanical computer nor the differential analyzer. After Demonstration Day the country was on a clear track to all-electronic, general-purpose, programable computing. There was no other way. There was no future. John, Pres, Herman, and some of the engineers fielded questions from the guests, and then the formal session finished. Everyone was reluctant to leave. John, Pres. Arthur, Harold and others were surrounded by attendees.

They circulated. They took turns running punch cards through the tabulator, and they had stacks of trajectory prints to share. They took the sheets apart and distributed them around the room. The attendees were delighted to receive a tracer, a memento of the amazing moment they just witnessed.

The women were not congratulated by any guest. Because none of the guests knew what they had accomplished. In the midst of the announcements and the introductions of Army officers, Moore School deans, and ENIAC inventors, the Programmers had been left out. “None of us girls were ever introduced as any part of it” that day, Kay noted later.

Since no one had thought to name the six young women who programmed the ballistics trajectory, the audience did not know of their work: thousands of hours spent learning the units of ENIAC, studying its “direct programming” method, breaking down the ballistics trajectory into discrete steps, writing the detailed pedaling sheets for the trajectory program, setting up their program on ENIAC, and learning ENIAC “down to a vacuum tube.” Later, Jean said, they “did receive a lot of compliments” from the ENIAC team, but at that moment they were unknown to the guests in the room.

At that moment it didn’t matter. They were concerned about ENIAC’s success and the success and success of their team. They were there to play an important role in making this a memorable day.

Engadget recommends only products that have been reviewed by our editorial staff. This is independent from our parent company. Affiliate links may be included in some of our stories. We may be compensated if you purchase something using one of these affiliate links. All prices correct as of the date of publication.