Belinda Hankins was first diagnosed with COVID-19 in spring 2020. Although she had symptoms like a fever and chills, as well as difficulty breathing, the most significant thing was her loss of sense of smell. Hankins remembers opening a canister of Tony Chachere’s creole seasoning, lowering her nose to take a whiff, and not smelling a thing. “That stuff usually clears the kitchen,” she says.

Two years later, her second infection was even worse. After 12 weeks of constant fatigue and aching joints, her doctor suggested that she be treated for long COVID. The lingering, sometimes full-body conditionAfter a COVID-19 infection, it can be a chronic condition that plagues people for years or months (SN Online: 7/29/22).

Late August saw Hankins, 64, join me in a small examination room to have her first in-person consultation at Johns Hopkins Post-Acute CoVID-19 Team clinic. Hankins, who is wearing a navy gown and a blue surgical face mask, sits across from Alba Azola in a comfortable chair. As they discuss Hankins’ symptoms, doctor and patient face each other, Azola occasionally swiveling her stool to tap notes into a computer.

Hankins’ symptoms are extensive. There are many symptoms, including brain fog, fatigue, pain and other issues. She’s depressed. Sleep doesn’t feel restful. She has trouble focusing, is lightheaded, and loses her balance often. She was exhausted and hurt even walking from the parking lot to the clinic. “I’m extremely exhausted,” she says. “I have not felt good in a long time.” Hankins, pauses, wiping away a tear. “I wasn’t like this before.”

Hankins is a retired digital marketing consultant. She was an avid cyclist and skier. She enjoyed dancing and traveling and she was keen to learn golf. She’s not sure what the future holds, though she tells me she still has faith she can be active again.

Treating people with long COVID can be complicated – especially for Hankins and those who have other medical conditions. She also has pulmonary hypertension, and fibromyalgia. It’s tricky to tease out which symptoms come from the viral infection. Azola’s approach is to listen, ask questions and listen some more. Then, she’ll zero in on a patient’s most pressing concerns. Her goal is to manage their symptoms. “How can we make their quality of life better?” she asks.

Overloaded system

On the afternoon of Hankins’ visit, it’s a warm summer day in Baltimore, blue skies laden with fleecy clouds. The vibe inside Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center’s labyrinthine halls is less sunny. There are bright lights, shiny floors and people waiting in line. Everyone I see is wearing masks.

Azola walks briskly with bright red glasses and meets me in my waiting area. Azola was a rehabilitation doctor who treated patients with strokes, spinal cord injuries, and other disorders before the pandemic. She still visits these patients most mornings. However, for the past two decades, she has been booking afternoons with COVID-19-injured patients.

She’s squeezed me in to talk about the Johns Hopkins PACT clinic, which opened in April 2020, around the time when the world hit one million confirmed cases. “To be honest, we didn’t know what to expect,” Azola says. Back then, most of the clinic’s patients were recovering from COVID-19 after a stay in the hospital’s intensive care unit. Now, at least half of their patients never got sick enough with COVID-19 to be hospitalized – yet still had symptoms they couldn’t shake. Azola and her colleagues could receive 30 referrals in a week. “It’s constant,” she says, “more than we can provide service to.”

Patients can wait longer as the number of referrals increases. PACT expanded its staff last summer to include therapists and physicians as well as other specialists. Azola states that the goal is to reduce wait times to less than two months. However it’s not uncommon for patients to wait up to four to six months.

The demand here and at clinics across the country isn’t likely to let up. Mid-November saw the United States report nearly 500,000 cases. 97.9 Million COVID-19 cases. It can be difficult to find long COVID numbers. nearly half of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 hadn’t fully recovered six to 18 months after their infection,According to a large Scottish study, published in Nature CommunicationsOctober 12, The United States has a more conservative estimate that there is more than 18 million Americans could be COVID for a long time.

“We are in the middle of a mass disabling event,” says Talya Fleming, a physician at the JFK Johnson Rehabilitation Institute in Edison, N.J.

Solution: Scattershot

There are approximately 400 clinics in the United States that provide care for long-term COVID patients.

While the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation did publish some guidelines, there aren’t any “gold-standard” therapies and no standard criteria for long-term COVID clinic performance. To share their experiences and to discuss best practices in long COVID treatment, the Academy brought together over 40 post-COVID hospitals, including Hopkins’ PACT clinic. “We’re kind of guiding each other,” Azola says. Other American clinics are more or less forging their own path.

Today, Azola and colleagues are focusing on their patients’ symptoms, a strategy other long COVID doctors and clinics are using too. “There is no one, singular long COVID experience,” says pulmonologist Lekshmi Santhosh. So doctors really need to take a “customized, symptom-directed approach.”

Santhosh was the founder of the OPTIMAL clinicUniversity of California, San Francisco Follow-up care for COVID-19 patients. Since 2020, she’s seen hundreds of patients, who can wait weeks to months for an appointment, like they do at Hopkins. One main question Santhosh hears from patients is: “When am I going to get better?” That’s hard to answer, she admits.

Scientists can’t yet predict how or when a patient will recover, and they don’t know Why long COVID strikes certain people while sparing others. At the moment, there aren’t any clear guidelines. “If you are young, you can get long COVID. Long COVID is possible even if there are no pre-existing medical conditions. If you’ve had COVID before, you still can get long COVID,” Fleming says. There are many more.

At UCSF, Santhosh says she’s seen it all. Long COVID can cause severe symptoms in patients over 75 who were hospitalized for COVID-19. It also affects a 35-year old marathoner whose persistent symptoms only developed after a mild infection. One patient may be affected by a whole host of health issues, while another patient might only have one.

“I’ve heard some weird things,” Azola says. Azola recalls one patient feeling like their bones were vibrating with a phone. One patient described feeling heavy, as if their legs were made from lead.

Long COVID’s scattershot symptoms currently require a smorgasbord of solutions. A doctor may prescribe pain relief for headaches. An inhaler that opens the airways can be used to relieve shortness of breath. Patients might see a therapist to help with their word-finding problems. Such symptom management is necessary, Azola says, because “we don’t have strong, randomized controlled trials to support the use of specific medications or treatments,” she says.

Developing effective therapies has been “frustratingly slow,” Santhosh says. Scientists are still trying to understand what’s happening in the body that spurs long COVID and lets symptoms simmer away unchecked. “The underlying biology is unclear,” she says. That makes it “unclear exactly what treatments might work.”

Long COVID’s biological underpinnings are a hot topic among researchers today, says Mike VanElzakker, a neuroscientist at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, and part of the Long COVID Research InitiativeA group that studies and treats the condition. Scientists have many hypotheses about the causes of long COVID symptoms. These include scarred lungs due to SARS-CoV-2 infection or the reemergence of another long-sleeping virus. One theory is that COVID-19 could impede the immune system and invite other microbes into harm. Another idea pins long COVID on caches of coronavirus hiding within the body’s tissues.

“It really does matter what’s causing these problems,” VanElzakker says. If doctors knew what’s driving a patient’s symptoms, they might be able to offer personalized treatments aimed at the illness’s root.

Filling the gap

You can find a variety of long COVID treatment options on Facebook pages and websites all over the Internet.

Vitamins, supplements, alternative medicines: general internist Aileen Chang in Washington, D.C. used to hear all the time from long COVID patients about therapies they’ve tried. Chang, along with colleagues, founded the George Washington Medical Faculty Associates COVID-19 Rehabilitation Clinic in the fall 2020. It was later shut down due to staff shortages. She recalls patients who flew to different countries to have their blood filtered and others who took “every sort of supplement you can imagine,” she says. “They’re looking for solutions.”

Opportunists have taken advantage of the lack of data to determine how long COVID treatments actually work. There are many unproven treatments that can cause serious side effects, and they can also drain patients’ finances. “They’re spending all this money on things they think will make them better,” Chang says, “but the truth is… we don’t know.”

Scientists know that long COVID treatments for patients are still in the early stages of development. There’s some evidence that getting a COVID-19 vaccine can improve long COVID patients’ symptoms, Despite this, it is still controversialResearchers published their findings in November in eClinicalMedicine. A series of sessions in which 100 percent oxygen is infused into a hyperbaric chamber could help to relieve fatigue and brain fog has been suggested by small clinical studies.

The U.S. National Institutes of Health initiated a huge research project last year on the long-term effects of COVID-19. The “The Associated with the…” RECOVER InitiativeThe project seeks to understand why some people develop COVID long term and to find the underlying causes. RECOVER had enrolled 10,645 out of the estimated 17,680 adults.

It’s a great initiative, Santhosh says, but it got rolling relatively late – well after long COVID had already upended many people’s lives. “We need… a lot more funding and a lot more therapeutic trials,” she says. Santhosh believes that doctors will soon have clear answers about which treatments work in the coming months and even years. “There are a lot of tantalizing biological leads,” she says. She also knows that the timeframe can be frustratingly long for patients and clinicians.

Real life

In the meantime, Santhosh, Azola and other physicians are borrowing strategies that help for other disorders – like myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Many symptoms are still unknown. Overlap with long COVIDScientists suggest September 8 as a possible date for finding answers to both disorders. Science.

One common approach isn’t a treatment like pills or surgery, it’s more of a shift in behavior: Don’t overdo it, Santhosh says. “We talk to our long COVID patients about this all the time, about the need to rest, to pace yourself and how to gently bring back your aerobic fitness.”

It is tempting for long-term COVID patients to feel like they can continue to live their life the way they did before being diagnosed. But that doesn’t seem to work for people with chronic fatigue, and “for some long COVID patients, it can actually make things worse,” she’s found.

Azola gives similar advice to Hankins. Azola walks away from the computer and turns towards her patient about half an hour into the appointment. “This is the part where people want to punch me in the face,” she tells Hankins, pushing her glasses up onto her head. “We don’t have a magic wand that makes [you] feel better.”

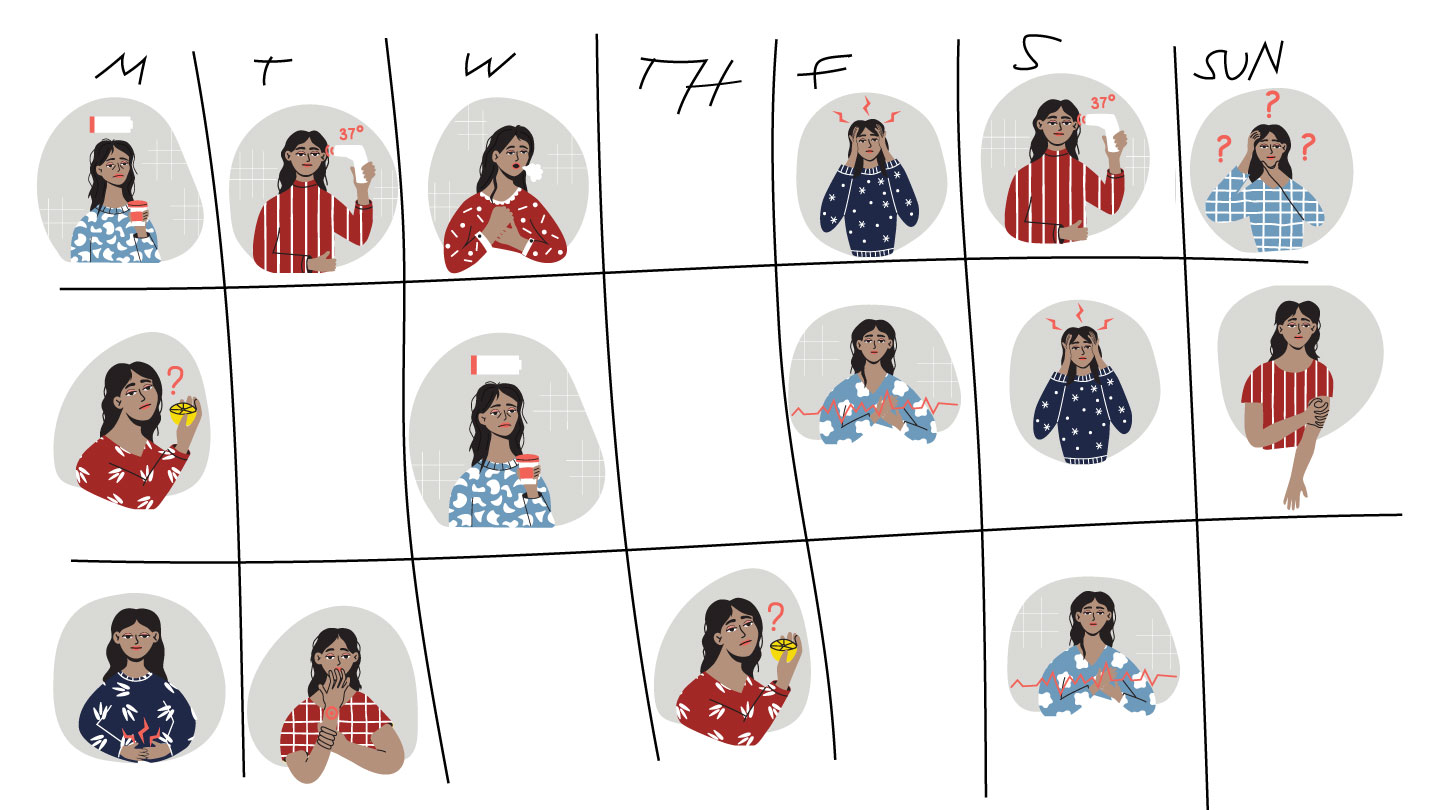

Instead, Hankins will need to check her body’s battery every day, conserve energy where she can, and build in opportunities to recover. Even small tricks such as sitting down while you shower or cooking can help patients conserve enough juice to get through the day. Azola hopes to get Hankins off the “corona coaster,” where patients can feel relatively good one day, and the next day, crash. Having energy levels constantly crater can erode a patient’s ability to live their lives, she says.

For the next 20 minutes, doctor and patient talk about how Hankins’ life has changed and what her next steps will be. In a week, she’ll meet with a neuropsychologist who will help her cope with her new reality; Azola also refers Hankins to a pain specialist.

The two women have spent about an hour together – a near-eternity for a medical appointment. For Azola, it’s time well spent. “The most important thing is to listen to patients and keep an open mind,” she says.

When I speak with Hankins nearly three weeks later, she’s still feeling hopeful. She’s met with the neuropsychologist, and will continue to receive follow-up care. Hankins hopes that a plan that includes all her conditions, including long COVID may help her feel better.

For now, she’s hoping that sharing her story will help others struggling with the illness. When she tells people she has long COVID, she says, “some of them don’t even think it’s real.”