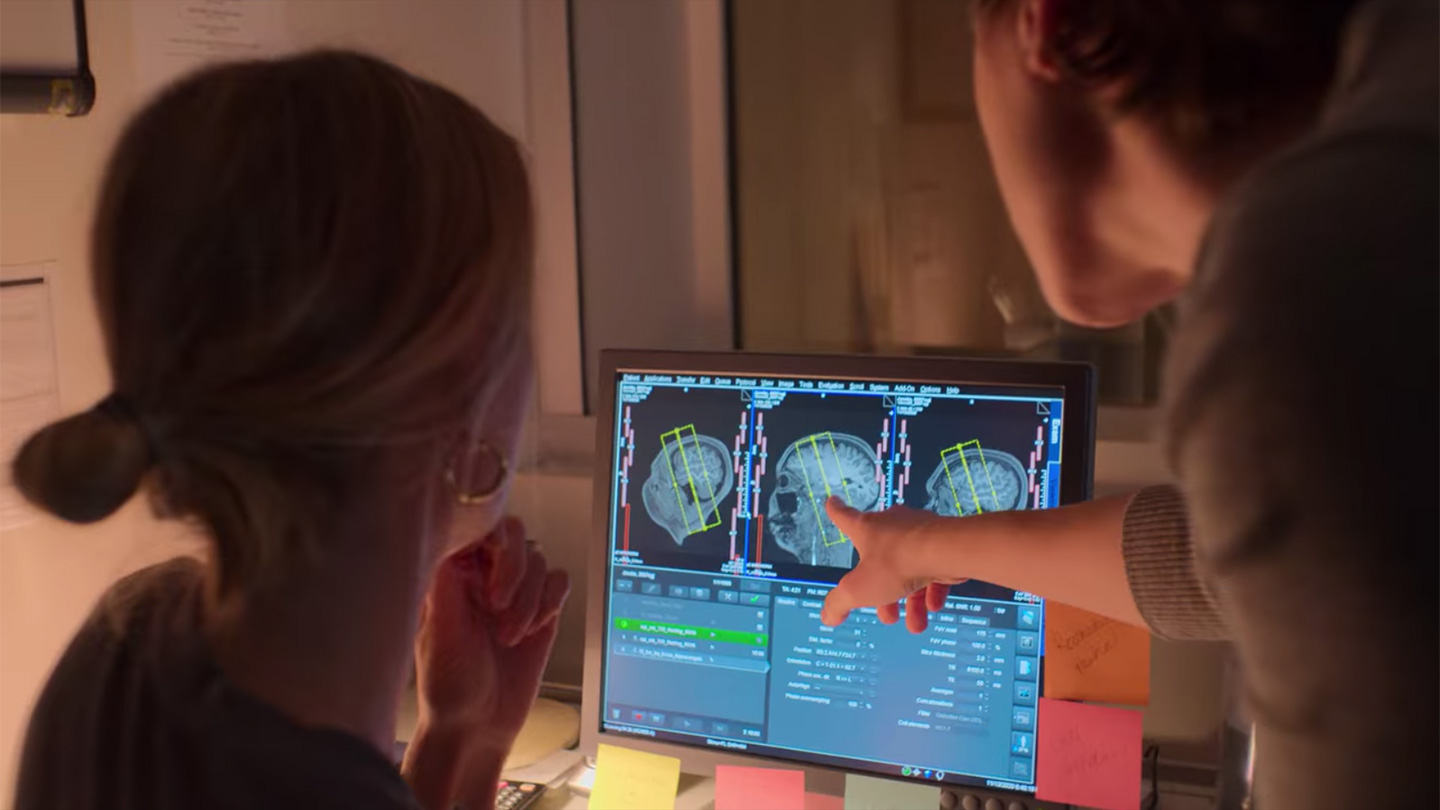

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was a new technique that allowed Emily Jacobs to study the brain during the 2000s. “Just like we have super powerful telescopes that can let us quantify the farthest reaches of the known universe, here we have this tool that could allow us to see the entire human brain and as a pulsing, living organ,” says Jacobs, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Neuroscientists gained new insight by measuring blood flow changes that are a proxy for brain activity. They were able to see how different situations lead to conversations between brain areas and how their intensity changes over time. “I was riding that wave of excitement,” Jacobs says.

But she soon realized there were big questions that weren’t being asked — questions important to half the world’s population. What effect do natural hormonal changes such as menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause have on brain communication? What about hormonal contraceptives such as the birthcontrol pill? Used by hundreds of millionsglobal population? What does all this mean for brain health, behavior, and the environment?

Big goal

The rise and decline of hormones has been a major reason why women have always been successful. Excluded from biomedical researchEven though hormones in men can fluctuate, they are still affected by these changes. Inadequacy in understanding female biology has been the result. Mental, PhysicalAnd Reproductive health care. “Science, and especially neuroscience, has not served the sexes equally,” Jacobs says.

With a range of tools — fMRI, other types of MRI and brain imaging, blood testing, neuropsychological testing, virtual reality and more — Jacobs’ lab is trying to fill in gaps in our basic understanding of how hormones act in the human brain. She is also using hormones to help answer bigger questions about brain change.

“What’s really special about Emily’s work is that she does it at so many different levels. It’s so multifaceted,” says cognitive neuroscientist Caterina Gratton of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. “She has multiple different types of brain measures, from the molecular all the way up to brain systems.”

Standout research

In a series of studies dubbed 28 and Me — for the 28 days of a typical menstrual cycle — Jacobs and colleagues closely monitored the brain of one woman for the duration of her natural menstrual cycle. Every 24 hours over 30 days, this 20-something woman’s brain was scanned, blood hormone levels checked and mood assessed.

As the woman’s estrogen levels peaked during ovulation, regions throughout the brain synced up. Regions in a critical hub known as the default mode network became close conversationalists. What’s more, one part of this network rearranged itself to create a new and transient communication clique. Gray matter temporarily expanded in a brain structure that is linked to memory and learning after ovulation when estrogen levels dropped and progesterone spiked.

When the same woman was examined a year later while on the pill, which quells progesterone, the changes weren’t observed.

The results were published in 2021 Current Opinion in Behavioral ScienceThese strong evidences support the assertion that Ebb and flow in sex hormonesJacobs and his colleagues believe that brain changes are a result of hormone fluctuations. They also observed a connection between hormone fluctuations as well as brain changes. in a male participant.

What’s next

The observations led cognitive neuroscientist Caitlin Taylor, a postdoc in Jacobs’ lab, to wonder how the brain responds to chronic hormone suppression from oral contraceptive use. The team is currently launching a large-scale studyYou can try to find out.

Jacobs hesitated at first to approve the research. Jacobs was worried that the research could be misused to limit contraception access. Eventually, she relented, because women “deserve to have science that can serve us,” she says.

Jacobs, Taylor and others are constructing a second effort to make large-scale research data widely available. The “The” University of California Women’s Brain Initiative, it aims to funnel records from the university system’s eight brain-imaging research centers into an open-access database. A woman’s brain will be scanned by one of these centers. Her medical data, brain-imaging data, and information regarding hormonal contraceptive usage will all be entered into the database. Once all eight centers are on board, there could be about 10,000 participants annually — way more than a single lab could recruit.

Jacobs believes the expected mountain of data will be a boon for researchers who are asking large and small questions about brain health. And she hopes it will improve women’s health care.

You would like to nominate someone on the next SN 10 List? To nominate someone, send their name and affiliation along with a few sentences about themselves and their work. sn10@sciencenews.org.